According to Google, the tool could generate 563 quadrillion faces.

Machine learning and artificial intelligence have, for a couple years, been hailed as the death knell to almost everything you can imagine: The information we consume, the way we vote, the jobs we have, and even our very existence as a species. (Food for thought: The stuff about ML taking over Homo sapiens totally makes sense, even if you haven’t just taken a huge bong rip.) So maybe it’s welcome news that the newest application of ML from Google, worldwide leaders in machine learning, isn’t to build a new Mars rover or a chatbot that can replace your doctor. Rather, its a tool that anyone can use to generate custom emoji stickers of themselves.

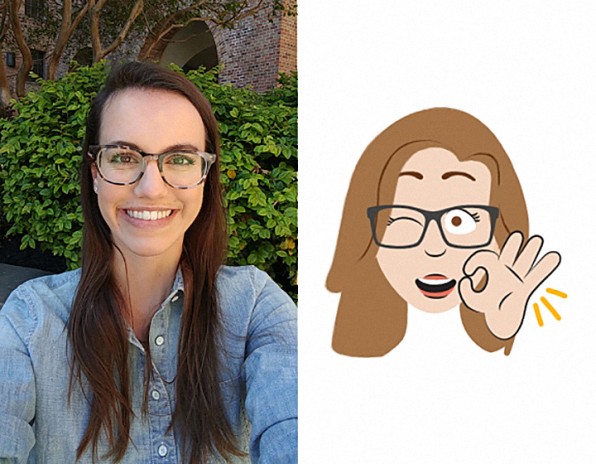

It lives inside of Allo, Google’s ML-driven chat app. Starting today, when you pull up the list of stickers you can use to respond to someone, there’s a simple little option: “Turn a selfie into stickers.” Tap, and it prompts you to take a selfie. Then, Google’s image-recognition algorithms analyze your face, mapping each of your features to those in a kit illustrated by Lamar Abrams, a storyboard artist, writer, and designer for the critically acclaimed Cartoon Network series Steven Universe. There are, of course, literally hundreds of eyes and noses and face shapes and hairstyles and glasses available. All told, Google thinks there are 563 quadrillion faces that the tool could generate. Once that initial caricature is generated, you can then make tweaks: Maybe change your hair, or give yourself different glasses. Then, the machine automatically generates 22 custom stickers of you.

The tool originated with an internal research project to see if ML could be used to generate an instant cartoon of someone, using just a selfie. But as Jason Cornwell, who leads UX for Google’s communication projects, points out, making a cartoon of someone isn’t much of an end goal. “How do you make something that doesn’t just convey what you look like but how you want to project yourself?” asks Cornwell. “That’s an interesting problem. It gets to ML and computer vision but also human expression. That’s where Jennifer came in. To provide art direction about how you might convey yourself.”

Cornwell is referring to Jennifer Daniel, the vibrant, well-known art director who first made her name for the zany, hyper-detailed infographics she created for Bloomberg Businessweek in the Richard Turley era, and then did a stint doing visual op-eds for the New York Times. As Daniel points out, “Illustrations let you bring emotional states in a way that selfies can’t.” Selfies are, by definition, idealizations of yourself. Emoji, by contrast, are distillations and exaggerations of how you feel. To that end, the emoji themselves are often hilarious: You can pick one of yourself as a slice of pizza, or a drooling zombie. “The goal isn’t accuracy,” explains Cornwell. “It’s to let someone create something that feels like themselves, to themselves.” So the user testing involved asking people to generate their own emoji and then asking questions such as: “Do you see yourself in this image? Would your friends recognize you?”

The project represents a long-running priority at Google—to figure out new ways that it can apply ML to broader and broader swathes of experience. The logic, for Google, is alluring: Google leads the world in ML, so if it can make ML into a must-have feature for apps and websites, then its products will be able to leapfrog competitors. Along those lines, Allo has become a test bed for all kinds of novel ML applications. “What we’re doing with Allo is trying to find all the ways that ML can make messaging better,” says Cornwell. “From saying the right thing at the right time to conveying the right emotion at the right time.”Which maybe sounds a little scary, as if Allo is trying to replace us as a conversational necessity altogether? But in practice, the applications seem almost inevitable. When someone sends you a message, Allo will suggest quick one-tap replies based on your conversation history. (For example: “That’s amazing!” if your friend sends you a photo of herself skydiving.) Or, if you’re having a group chat, Allo uses ML to bring up an automatic, bespoke list of funny GIFs to send in response. The idea is, it’s augmenting your abilities, rather than taking them over. “We’re thinking along the same lines in lots of other ways as well, where art and ML meet,” says Cornwell, though he declines to say what, exactly, Google has in store. Daniel, however, does admit there are new emoji styles to come, done by different artists, with entirely new takes. So many there will be a new pack that lets you recreate yourself as a dog? (Please, let it be so.)

All told, Daniel points out that the project represents a new intersection for art and engineering. After all, we’re just beginning to scratch the surface of what ML can do for art. If Leonardo da Vinci were alive today, it’s hard to believe that the Mona Lisa would be a painting. Instead, maybe it would be an image of the viewer herself, remade as an iconic everywoman with a mysterious expression that spans across cultures and generations. But we’ve yet to see anything that cool at the Whitney Biennial. Instead, it’s probably up to companies such as Google to push the boundaries. Which is what brought Daniel, who has been an outspoken critic of the triumphal solution-ism of Americas tech-design scene, to the Google fold: “I’m interested in the intersection of how engineering works with art, and having a platform where the work we create isn’t just content, but the product itself.”

–

![[Image: Google]](https://assets.fastcompany.com/image/upload/w_707)