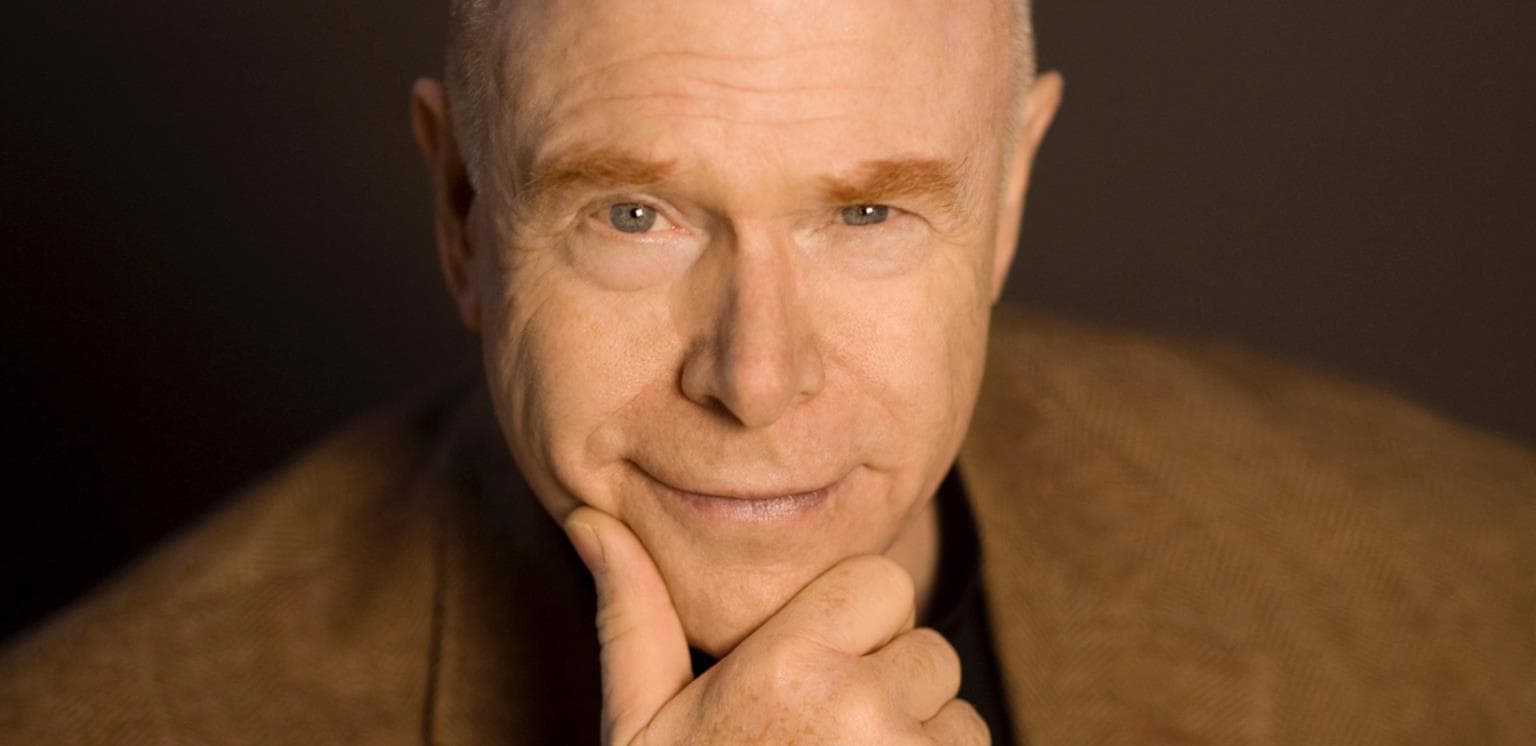

Business leaders often misunderstand the actual meaning of strategy, Richard Rumelt argues in his new book,

The Crux: How Leaders Become Strategists (Public Affairs, May 2022). In this episode of the Inside the Strategy Room podcast, the long-time professor at the UCLA Anderson School of Management and former president of the Strategic Management Society talks with McKinsey senior partner Yuval Atsmon about the parallels between mountain climbing and strategy, the difficulty in committing to choices, and strategy sessions as “success theater.” This is an edited transcript of the discussion. For more conversations on the strategy issues that matter, follow the series on your preferred podcast platform.

Yuval Atsmon: What are the differences between what you call good strategy and bad strategy, and why is the latter on the rise?

Richard Rumelt: Certainly, the trend over the past 30 to 40 years has been in the direction of bad strategy. It’s a social contagion of sorts. In fact, my provisional title for the book was Breaking the Bad Strategy Habit. Many companies treat strategy as a way of presenting to the board and to the investing public their ambitions for performance, and they confuse that with having a strategy. Some of it is the victory of finance as the language of business because we talk about shareholder return as the ultimate measure of success. Executives end up saying, “Our strategy is to achieve these results,” but that is not strategy.

Strategy is problem-solving. It is how you overcome the obstacles that stand between where you are and what you want to achieve. There are, of course, companies and individuals with brilliant insights into what’s happening in the world and how to adapt to or take advantage of it, but I am often asked to participate in strategy sessions, and a lot of them are awfully banal. In a typical session, the CEO will announce certain performance goals: “We want to grow this fast, and we want to have this rate of profitability.” Maybe they will throw out some things about safety and the environment, and that’s their strategy. But that’s not a strategy—that’s a set of ambitions.

Strategy is how you overcome the obstacles that stand between where you are and what you want to achieve.

Nowadays, I first ask, “What are your ambitions?” If you have six or seven senior leaders in the room, you get a big spread. It’s not just about shareholder returns; it’s about success, and respect, and responsibility. That’s fine. We all have ambitions. In The Crux, I write that when I was 25, I wanted to climb the big mountains of the world. I wanted to be a professor of business and an inspiring teacher. I wanted to marry a beautiful woman and have successful children. I wanted to drive a Morgan Plus 4 Drophead. Those were desires. Could I accomplish them all at once? Of course not. The beginning of strategy is, which of these ambitions can we make progress on today or in the near future? Then you formulate an action plan. This gap between action and ambition is where most bad strategies come from. Bad strategy is almost a literary form that uses PowerPoint slides to say, “Here is how we will look as a company in a year or in three years.” That’s interesting, but it’s not a strategy.

Yuval Atsmon: I find it’s difficult for people, both in business and in their personal lives, to commit to choices. At McKinsey, we define strategy as making choices ahead of time in the face of uncertainty. If you can keep changing the decision, it’s probably not a strategic decision. Many executives try to keep options open to delay those choices.

Richard Rumelt: Yes. When you commit to the left road in the woods instead of the right road, you are killing off things that might have been. That’s painful. In 1993, I was climbing the Dômes de Miage, a very narrow ridge in France. I was up there with [Canadian business professor] Henry Mintzberg, and if one of us were to fall to one side, the other was supposed to jump to the other side to balance us. At one point I caught my crampon point in my pant leg, and I stood there for a moment before pulling that foot up and putting it down. And I had this epiphany: “I’m in my late 50s. What am I doing up here? My wife is in Massachusetts. My daughter is graduating college. I have doctoral students who need advice, I have a book I want to write.” I began to realize that climbing is not a good choice for me.

So, I stopped doing technical climbs and became more of a hiker. It was a painful choice. When I see pictures of that mountain, I still feel a pang. When you decide to commit your energy to A rather than B, it is not comfortable, so executives instead generate lists of priorities. I had a client with 12 priorities on their list, which violates the definition of the word priority, which means “first.” You don’t want to be on a plane and hear an air traffic controller say, “I’m giving priority on Runway 3 to the following list of airplanes.” Having a list of priorities is a way of finessing the fact that we don’t want to make a choice. It also reflects the tendency to try to include everyone, all the roles and activities, in the strategy. I call that “the public face of strategy.”

There are two origins of the word strategy, one going back to the Greeks and the other to Napoleon’s activities, but whatever its source, it has to do with a focus of strength against weakness. In business, it’s a focus of strength against opportunities or problems. That focus of strength is essential. If you focus resources on a weak point, even if it’s a great opportunity, you are not acting strategically.

Yuval Atsmon: How should companies approach long-term strategies in a world that’s increasingly dynamic?

Richard Rumelt: I tend not to emphasize long-term strategy. If it’s appropriate in a given situation, I call it a “grand strategy” or talk about mission. I’m not sure you can have a long-term strategy in today’s world. Going back to mountain climbing, I see strategy as a journey. You look at a mountain and say, “I think this ridge is the way to go.” You go up and you find the ridge blocked, so you say, “I will traverse on this ledge.” Then you look up and say, “Now I’m going up this crack. I think it will lead to another ledge.” You find your way. The long-term there is getting to the top, but that’s turning strategy into ambition again. The strategy is how you get to the top, and you do that—as a company, as an individual, or as a nation—by solving problems. Companies typically evolve through their responses to challenges, just as, according to Arnold Toynbee, civilizations evolve through successive challenges and responses.

Yuval Atsmon: I would add that higher volatility makes strategy even more of a problem-solving practice because you need to make decisions at a quicker pace and more often than in the past. And what matters is not so much understanding the trends but spotting the discontinuity in trends, because it’s the change that presents opportunities and challenges. That requires both relating the change to its potential impact on your business and galvanizing action to address the challenge.

Richard Rumelt: Yes, but we find game changes difficult. For 30 years, the basic trends were increasing globalization and increasing specialization, with pieces of value chains dividing into smaller pieces: you go to one place to evaluate products and another place to buy the product and a third place to ship the product. That’s expected in an open system, but are we entering an era when we have to rethink how we source and distribute? Many trends right now suggest that we are at an inflection point and things will be different in the future.

Yuval Atsmon: Your book does not suggest that in a more complex world, strategy becomes more difficult. Instead, you tell readers to go back to the essence—the crux—of what matters most or the point of leverage that companies can use to differentiate themselves.

Richard Rumelt: Right. One reason many companies’ strategies are banal is that they try to do too many things at once. One principle I expound is that if you are to expend energy and talent on solving a problem, it had better be, A) a very important problem, and B) a problem you can actually solve. There are problems we can’t solve, so let’s defer those to next year and instead work on what we can deal with. I have yet to find a company that will abide by my advice and focus on one problem. They always want two or three.

The crux of a mountain climb is the hardest move or segment, and you practice getting over that crux in order to accomplish the climb. The advice that comes from that is, “Don’t attempt a climb if you can’t handle the crux.” In business or national-security terms, that means, “Don’t tackle a problem if you can’t handle the hard nut at its center.” The successful strategists ask, “What’s the crux of these problems? Can I get through them? And if so, which of these problems is worth putting our resources toward?”

Yuval Atsmon: Many organizations emphasize resilience these days. What are your thoughts on integrating resilience into a strategy?

Richard Rumelt: In traditional strategy, we studied products, we studied markets, and we studied customers, then we tried to see where we had an advantage and committed resources there. What that leaves out is organizational functioning. Some people say, “Strategy is important, but it’s really about execution.” That’s silly. That’s like saying, “We have a military strategy, but our soldiers are too fat to walk.” Execution is part of strategy, of course. Strategy is about what is important and the challenges you face. If one of these challenges is that the organization is dysfunctional, then that’s strategic. If your managers are not managing properly, if the organization lacks the resilience it needs for the business it’s in, that is a strategic issue.

Now, do all organizations have to be resilient? No. Some companies are in businesses where things change almost every week, and they need to be resilient and adaptive. If you have been making brand-name candy bars for 100 years, I’m not sure how resilient you have to be—you are in a stable market niche with a very stable business. The hard part comes when you see a new opportunity you can’t resist—and that opportunity is in a differently paced world. Then you need more resilience to deal with attacks and responses and change while also developing a different operating pattern from the past. That’s a tough situation.

Yuval Atsmon: These days, companies are planning for different scenarios. It’s very hard to make predictions right now, but times of volatility are opportunities, to your point, to apply strength against weakness. So for some companies this is an opportunity to make bolder strategic bets.

Richard Rumelt: I like your expression “strategic bets” because business is about making bets to some extent. There is an Arab saying, “He who predicts the future lies even if he tells the truth.” What will be the top five agenda items in 2027? Will sustainability be one? Will equity and inclusion? Deglobalization? Yes, probably. Now go forward another five years, to 2032. History shows that the top five will not be the same. There are long-term things you can bet on. Age distribution of the population is pretty fixed, and for much of the world, this means a coming imbalance of too many old people and not enough young people. We can predict that because it’s already here. Birth rates in Germany are far below replacement birth rates. You know there will be a shortage of young workers. The social and technical stuff, that is much harder—nobody forecast the addictive quality of social media. But strategy is not about forecasting; it’s about dealing with problems you can recognize.

Yuval Atsmon: In your book, you talk about people preferring to hear good news—what you call “success theater.” To countermand that, you suggest they ask simple questions like, “What about that plan is difficult?” As strategists, we should quickly get to the core of the challenge that must be overcome, right?

Richard Rumelt: The first step people struggle with is accepting the idea that strategy is about overcoming challenges. I worked with a government group that spanned 12 different agencies and they had a strategy that had 22 “priorities.” They insisted they could achieve them, and I kept saying, “But you have to deal with why that’s hard. If it was easy, it would already have been done.” They worried that if they said, “We have a problem,” Congress might not give them money, so they had, in this case, an ambition theater focused on “We can do it!”

Likewise, many businesspeople believe it’s bad to talk about problems. Peter Drucker said that you shouldn’t focus on problems but opportunities. It’s sort of this macho tradition, and I love that, but if we are dealing with strategic stuff, we have to deal with the reality that it’s difficult. For example, how do we deal with our technology not being up to par? You can’t transition to better technology without exploring why that is difficult, organizationally and intellectually and in terms of skills.

Yuval Atsmon: What’s your advice for getting the entire organization involved in strategy development and then execution?

Richard Rumelt: I’m not a big proponent of strategy as a giant democratic action where everybody contributes. If you have a dysfunctional organization, then the wisdom of the various organizational levels is not being digested by the leadership.

There are two types of errors. One is where you don’t involve the front lines, and the other is where the front lines don’t understand the strategy. If the strategy is focused energy on a critical thing, then it can’t be what everybody wants and everybody gets a little piece of what they do included. The hang-up is when you’re disconnected from what is happening in your business and don’t understand the nature of the problem partly because of the success theater, where business managers only talk about their successes and opportunities.

Yuval Atsmon: What are the best ways to engage the board in strategy development?

Richard Rumelt: It’s interesting that boards do not typically have strategy committees. “Strategy, that’s the CEO’s job.” Boards may not need strategy committees, but they do need a sense of best practice, just as we have well-established best practice in accounting: here is the way results should be reported and analyzed. We lack that maybe because there are too many conflicting voices on what good strategy is.

The big dysfunction that happens on boards is we say, “Let’s bring in outsiders, people with different backgrounds and representing different social, political, and economic interests.” That’s great, except now you have a roomful of people who don’t understand the business. The language these people have in common is financial accounting, so that’s what they concentrate on. As long as things are going great that’s fine, but when you begin to get into trouble, the problem-solving is absent at the board level. All the board can do is replace the CEO. The role of the board vis-à-vis strategy is one we have not yet sorted out as a society.

Author Name: Richard Rumelt

This article first appeared in https://www.mckinsey.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +971 50 6254340 or engage@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com/story