The company, whose CEO Travis Kalanick has resigned, masterminded the dark arts of manipulative UX.

I’ll never forget my first Uber. As cheesy as that sounds, I’m sure the feeling is shared by many of us of a certain age. Finding myself stuck on the sleepy streets of San Francisco’s Nob Hill after midnight, not a cab in sight, I hit a button on my phone, a car drove up a few minutes later, and I realized city life as I knew it would never be the same.

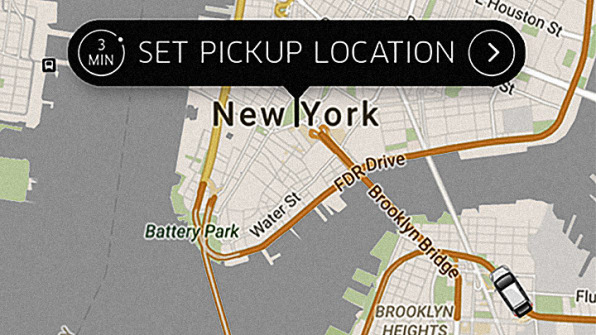

This is the power of design. Uber hid the complicated logistics of connecting cars on the move with customers who might appear anywhere on the map with the simplest of apps. I saw my car. And my car saw me. The mind-numbing calculations behind the scenes were invisible. It all felt, to borrow a word that’s been horribly over-used in the smartphone age, like magic.

Yet it’s quickly become clear that Uber’s design legacy is more of a mastery of the dark arts. The departure of CEO Travis Kalanick this week caps a year during which countless insider reports revealed that the company is, in a way, more incredible than any of us imagined. However, it’s incredible specifically for its unprecedented customer and driver manipulation, along with its leveraging of data to sidestep authorities and whistleblowers.

Perhaps none of this will actually change with Kalanick’s departure, but 20 years from now, we will look back at Uber with the same unsettling reverence that we do an intricate machine of war. More than any other company before, Uber weaponized UX to conquer the digital and physical worlds.

Uber started as a black car service for the Valley elite. The approach was standard from any branding playbook: Launch a company marketed to VIPs, then reveal to the middle class that they can have a piece of the high life, too. And who didn’t want a personal car service arriving at their door for less than the price of a smelly taxi?But behind the scenes, Uber leveraged the data of its riders and drivers to control both groups of users. Reports of a “God View” revealed that Uber execs could see the position and identity of any rider at any time. And it wasn’t just a means for execs to stalk Beyoncé, either. Uber’s rider data gave it extremely personal information on journalists. One executive floated the idea of spending $1 million to hire a team to look into just this information, including the “personal lives” and “families” of journalists, to arm the company with blackmail fodder against its critics. The company also deployed a project dubbed Greyball, which identified certain city officials and authorities, flagging their accounts–sometimes by looking at a customer’s credit card to see if it was linked to an organization like a police credit union–specifically to stop sting operations targeting Uber’s often less-than-legal operations.

Greyball was used for more than tracking individuals. Uber realized that it could actually be deployed to geographic regions, changing the very functionality of Uber for specific segments of the population. For instance, using geofencing–which draws invisible boundaries on an app’s map–Greyball could spot groups frequenting courthouses or police stations. The feature created fake “ghost cars” to confuse regulators who might be operating stings.

Geofencing also helped Uber deceive Apple itself. Uber had been “fingerprinting” iPhones, leaving tracking files behind even after the Uber app had been deleted, despite Apple forbidding the practice. So it geofenced Apple’s campus–on the orders of Kalanick himself–to hide these practices from Apple engineers, presumably just deleting those hidden files on any supposed Apple employee’s iPhone. (For the invasive violation, The New York Times reports that Kalanick got a slap on the wrist from Tim Cook.)

But Uber’s dark manipulation engine was especially inescapable for drivers.

Above all else, Uber wants to keep cars on the road, and it developed a remarkable cadre of data-powered UX tools to do so. Just like Netflix loads that next episode of House of Cards, Uber automatically queues up a driver’s next trip before their last one is done, urging them to binge on work. Those who try to close the app are often pinged with a notification that they’re approaching an earning milestone–and drivers will be pinged in the morning with all sorts of enticing alerts to get them driving again. Perhaps the most unsettling twist is the gamification of rider goodwill–which may serve as a substitute for better driver compensation. When you compliment an Uber driver in the app, they will often receive badges like Above and Beyond. These happy pixels motivate people to work for something that literally disappears once they close the app.

Uber was not the first company to use gamification or psychological manipulation to get a user to do things they wouldn’t normally want to do. And certainly, it was not the first company to mine user locations or leverage that data for more profit. But Uber was the first to layer all of these practices together in a strange new interactive symphony, which hit us deep in the stomach so that we’d sway to the beat.

What happens now? Kalanick may be out as CEO, but Uber’s code and interface are still humming along. Many of the aforementioned policies are still intact.

Indeed, reports of Uber’s dark patterns have been growing for years now, and while data is scarce, none of these practices seem to have brought the company to a halt like the events of the past few weeks. Instead, Uber’s board eventually turned on Kalanick after months of simmering #DeleteUber outrage that began Uber attempted to profit from the travel ban protests in January and reached its crescendo after damning reports of gender discrimination, harassment, and toxic bro culture.

So we shouldn’t assume that Uber’s dark patterns will suddenly change under new management. After all, they’re precisely what built the $50 billion company that Uber is today–with or without its CEO.

–